Listening for the Voice Behind the Letter of Tradition

Kang Youwei's Quest for a Fulcrum Point

It arrived like an incoming tide. First lapping on the glistening sand, then taking the shoreline by inches, filling runnels, smoothing footprints, and encircling the fixed boulders of ancient truths. Then, like a wind-driven king tide, it surged past established high-water marks, flooded embankments, and lifted every beached boat.

China awakened from its ancient cycles of dynastic eras to find that it was now in the nineteenth century, a universal era—named, calibrated, and celebrated in the West. It was a bedeviled thing, weirdly unsettling, advancing by the ceaseless metronome of the clock. You could feel it in the coastal cities. But for many Chinese across the Middle Kingdom, the awareness of their place in this chronology came by fits and starts.

Historically, China’s conquerors—whether Turk or Manchu—had adapted to Chinese ways. The culture had enfolded them. But with the nineteenth-century incursion of the West, China was contending with cultures that were geographically remote, transported over the seas, and bursting through the integuments of the empire.

The old trading “factory” of Canton had been a firmly corked jar of commerce. But the treaty ports that followed were beachheads of a foreign modernity. They pulsed with a dynamism that was both resistant to assimilating Chinese culture and powered by transformative technologies and ideas. China’s Great Wall to the north was now a derelict monument, useless in holding back these intruders, who were now penetrating into the heart of the empire.

While the West had incrementally given birth and adapted to this new world—we generally call it modernity1—China had the full package dropped on its doorstep. And so too Japan. But Japan had been quick on its feet, had immediately gone to school and cracked the code of this new thing. And with the Meiji Restoration (beginning 1868) it was rapidly implementing the tools of modernity to its own advantage. What Japan had, China did not. And what better target for Japan’s newfound power than the now senescent giant to its west, China. The so-called Sick Man of Asia.

By the late nineteenth century, the crisis was reaching a tipping point. China’s military defeat in 1895, by its East Asian neighbor, Japan, had rammed home the point. It was a stake in the heart or her national pride. Japan’s Meiji era had empowered a rapid development of technology, with no small part funneled into weaponry. But for China, the manageable options were shrinking rapidly.

Within the Palace Walls

Between the spring and autumn of 1895, within the Bejing palace walls, the Guangxu Emperor was carefully poring over a newly translated book from English. It was an eye-opening account of the emergence of the Western world from its own troubled times.

The book began: “At the opening of the nineteenth century all Europe was occupied with war.” But then there unfolded a new reality that was now hurtling into the future: steam-driven engines on land and sea, photography, electricity, printing presses, advanced weaponry. Of the telegraph, the emperor would read:

It is the first human invention which is obviously final. In the race of improvement, steam may give place to some yet mightier power; gas may be superseded by some better method of lighting. No agency for conveying intelligence can ever excel that which is instantaneous. Here, for the first time, the human mind has reached the utmost limit of its progress.2

And then, near the conclusion of the book, there was this:

Human history is a record of progress—a record of accumulating knowledge and increasing wisdom, of continual advancement from a lower to a higher platform of intelligence and well-being….

The nineteenth century has witnessed progress rapid beyond all precedent, for it has witnessed the overthrow of the barriers which prevented progress. Never since the stream of human development received into its sluggish currents the mighty impulses communicated by the Christian religion has the condition of man experienced ameliorations so vast…. The growth of man’s well-being, rescued from the mischievous tampering of self-willed princes, is left now to the beneficent regulation of great providential laws.3

The book had been translated by the Welsh Protestant missionary Timothy Richard, and it was Robert MacKenzie’s The 19th Century: A History. It was published in Shanghai by the Society for Diffusion of Christian and General Knowledge among the Chinese, an organization which Richard served as an “honorary secretary.” And the newly formed Hanlin Reform Society had distributed numerous copies among the court intelligentsia.

In fact, a small cadre of Protestant missionaries was actively in conversation with the intellectuals, state ministers, and princes in Beijing. Timothy Richard had developed a relationship with Kang Youwei and his associate Reformer Liang Qichao. And it was reported that Kang’s memorial on reform, which he had submitted to the throne, included many ideas that were found in the publications of the Society. Richard’s associate, the American Presbyterian Gilbert Reid, focused most of his efforts on pursuing conversations with the highest officials and princes. Both Richard and Reid had refashioned their missionary efforts, from reaching the common people to influencing China’s leaders. And in this they married the gospel with science and technology. Also active in these circles was the Methodist Episcopal missionary Young J. Allen. Kang Youwei would later say, "I owe my conversion [to reform] chiefly to the writings of two missionaries, the Reverend Timothy Richard and the Reverend Doctor Young J. Allen.”4

Excerpt from the October 31, 1895, Annual Report of The Society for the Diffusion of Christian & General Knowledge among the Chinese

Within the Halls of Confucian Learning

Meanwhile in the halls of Confucian learning, there was an ongoing debate. How might the Confucian worldview and statecraft be maintained in the face of these new challenges? Might it be possible to hold a distinction between Confucian essence, its ti (or “substance”), and its utility, its yong (or “function”). Could the substance of the Confucian tradition coexist—be wed even—with the practical utility of Western technology and its accoutrements?

As we might expect, Confucian traditionalists marshaled their considerable intellectual defenses against any East-West syncretism. One point of view was that since the pre-modern era, China’s tradition had in fact encompassed scientific advances. Examples corresponding to some of the West’s science and technology were embedded in China’s history. And specimens could be hauled out from the cultural storehouses for exhibit. The traditionalist strategy leaned into neutralizing any notion of indebtedness to the West.

But if this heritage were to be granted, why then had China not developed its science and technology to greater advantage? Well, replied the traditionalist, it had been shown to be wanting, a mere trifle in the sublime landscape of Confucian wisdom.

But this answer did not—could not—satisfy reformers. For the imperative of adopting Western science and technology was now self-evidently clear. And it was equally clear that the Confucian mind had fallen short in its ability to foster and sustain China’s own scientific and technological breakthroughs.

Moreover, the yong of practical utility was now riding in on a flood tide of irresistible technological advances, including military innovations and weaponry that must be adopted for China’s own defense. And there were the commercial enterprises as well, with their calculated efficiencies and administrative methods. The latter was displayed in the Qing’s Imperial Maritime Customs Service, which from 1863 was run by Robert Hart, a British citizen.

As Vera Schwarcz observed:

The ti-yong formula became more complicated in practice…. Political reformers discovered that embedded in Western “means”—that is to say, in technological expertise—were distinctive goals that were inimical to the fundamental values of Chinese, or more precisely Confucian, civilization.5

The yong of foreign practical utility threatened to engulf the ti of Chinese essence. And this new context of Western practical and utilitarian ideas set up a new framework for reading Confucian texts, with a consequent shift in the layers of tradition. Things would not stay the same. Joseph Levenson puts his finger on what was troubling the traditionalists:

A gain in knowledge is always the transformation and the recreation of an entire world of ideas. It is the creation of a new world by transforming a given world. If knowledge consisted in a mere series of ideas, an addition to it could touch only the raw end… But, since it is a system, each advance affects retrospectively the entire whole, and it is the creation of a new world.6

Within the Spring and Autumn Annals

While some voices, such as Sun Yat-Sen, were calling for the overthrow of the Qing rule, Kang Youwei, the “modern sage of China,”7 took a reforming approach. For this reform to have any traction, he must appeal convincingly to the corpus of Confucian thought. But his was not the path of close textual work, of weighing words, analyzing syntax, and excavating layers of tradition. That was the way of the Old Text school.

Kang’s approach to reforming China’s imperial rule was to divine within the treasury of Confucian wisdom a neglected current favoring development and progress. For Kang Youwei and the New Text school, the Five Classics were written by Confucius. They were not just an edited transmission of previous historical traditions, as the Old Text school would have it. And the Spring and Autumn Annals provided the key to the other texts. There, in Kang’s hermeneutic, he found the “subtle words and profound meanings” that called “for the reform of institutions.”8

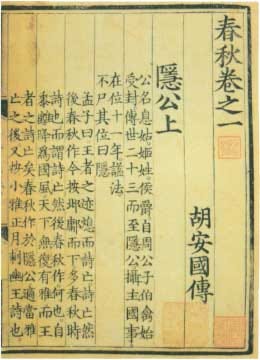

Opening Page of the Spring and Autumn Annals

Kang had found his platform on which he mounted his argument for a progressive Confucius.

He made Confucius the prophet of progress to a utopian Confucian future, towards which the West, with its modern values, was also on its way. K’ang set a course for Chinese history in the stream of western optimism, and he called it a Chinese stream.9

As Levenson notes, Kang shared something with the ancient rabbinic interpreters, who took for granted that any subtle truth of Torah disclosed to a later interpreter had already been known to Moses.10 And as Kang divined deep and subtle meanings in the old, the effulgence of Confucius’s glory imbued Kang’s vision with the authority of tradition.

In Levenson’s estimation, the Old Text critics never understood “the real question” the New Text school was asking: “Not ‘What does Confucius say?’ but, ‘How can we make ourselves believe that Confucius said what we accept on other authority.’”11 And so for the Old Text school to debate with the New Text school the precise meaning of a given word or sentence in the classics was, perhaps, quite beside the point.

One last thing, which I will be exploring in the future: The very wrestling with tradition and modernity that China’s scholars and leaders were undertaking in the 1890s (and which would continue into the early twentieth century), would have its counterpart in the Protestant missionaries wrestling with modernity in the 1920s and 30s. And a significant chapter in that story would be worked out in China.

In the next post I will explore Kang Youwei’s surprising vision of reform.

But Don’t Leave! Here’s an Addendum.

In a recent posting on the Substack Sinification, we find a sample of the long memory of China, its keynote of shame and honor, and how it reaches into the twenty-first century. The context is the 2008 Beijing Olympics, which showcased China’s prosperity and power. And yet cracks in the facade generated controversy.

This controversy gave rise to a historiographic framework known as "The Three Afflictions" (三挨), that links China's past struggles to successive generations of CCP leadership. Mao Zedong confronted the first affliction of “being beaten” (挨打), lifting a semi-colonial, semi-feudal China from foreign humiliation and enabling it to "stand up" (站起来). Deng Xiaoping tackled the affliction of “being starved” (挨饿), transforming a backward, impoverished nation into the world's second-largest economy and ensuring it "became rich" (富起来). Today, Xi Jinping faces the third and perhaps most complex challenge: “being scolded” (挨骂; translated below as “taking flak”). His mission is to ensure that China "becomes strong" (强起来), capable of commanding respect and telling its own stories on the world stage.

And then this:

Wang and Zhang have built their careers on Xi Jinping's assertion that “the world is undergoing profound changes unseen in a century,” encapsulated in the belief that “the East is rising, and the West is declining.” In his column, Wang writes that China's advancements in technology, infrastructure, and governance often make overseas cities seem like lower-tier Chinese ones, “A sense of superiority naturally arises among Chinese people.”

Jürgen Osterhammel alludes to “dozens of theories of modernity,” and that sounds about right. Today we also find the idea of “multiple modernities” coexisting in the world (S. N. Eisenstadt). Osterhammel comments that in the nineteenth century, “in the non-Western world the characteristic features of modernity are recognizable only in Japan, if only with many special twists.” See Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century (Princeton University Press, 2014), Conclusion: 2. Modernity.

Robert MacKenzie, The 19th Century: A History (T. Nelson and Sons, 1880), 193. The Eighth Annual Report of the Society for the Diffusion of Christian and General Knowledge among the Chinese, for year ending October 31st 1895 (Shanghai: Noronha & Sons), 9, reported: “One of our publications the History of the Nineteenth Century has been studied carefully by the Emperor during the last two months. The Hanlin Reform Society have ordered 100 copies of it, and Christian books of our Society are also being studied now by some of the Tutors of the Emperor and by several of the leading mandarins in the Capital.” See Timothy Man-kong Wong, “Timothy Richard and the Chinese Reform Movement” Fides et Historia 31.2 (1999): 57.

MacKenzie, The 19th Century, 460.

Quoted in Timothy Man-kong Wong, “Timothy Richard and the Chinese Reform Movement,” Fides et Historia 31.2 (1999), 47, where he cites Cyrus H. Peake, Nationalism and Education in Modern China (New York, 1932), 15, as quoted in Immanuel Hsu, The Rise of Modern China 4th ed (Oxford University Press, 1990), 358. For Gilbert Reid and Timothy Richard in Beijing, see Tsou Mingteh, “Christian Missionary as Confucian Intellectual: Gilbert Reid (1857-1927) and the Reform Movement in the Late Qing” in Daniel H. Bays, ed., Christianity in China: From the Eighteenth Century to the Present (Stanford University Press, 1996), 73-90.

Vera Schwarcz, The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and the Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919 (University of California Press, 1986), 5.

Joseph Levenson, Confucian China and Its Modern Fate: A Trilogy, 3 vols. (University of California Press, 1968), 1:64. Levenson’s is an older work, inevitably superseded by more recent scholarship, but still valuable. The point Levenson makes above has some parallel with Charles Taylor in A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007), 22, 26-29 et passim. The “subtraction stories” of modernity and secularity are mistaken. A society does not simply slough off “certain earlier, confining horizons, or illusions, or limitations of knowledge” to arrive at a bedrock that was there all along. In fact, the result is a new construction.

Kang is referred to as such in The Eighth Annual Report of the Society for the Diffusion of Christian and General Knowledge among the Chinese, for year ending October 31st 1895, 9.

Hui Wang, The Rise of Modern Chinese Thought (Harvard University Press, 2023), 497. Wang’s book demonstrates—at great length and learning—the continuing relevance of Kang’s thought for today.

Levenson, Confucian China, 1:81-82.

Levenson, Confucian China, 3:36.

Levenson, Confucian China, 1:87. Is this unduly cynical? Perhaps. But I think it names a common phenomenon in interpreting canonical texts in changing times. One can observe the same sort of thing going on in biblical interpretation today. And, I would add, it finds parallels in US constitutional interpretation, where culturally desirable rights may be discovered hiding in the “penumbra” of the text.

Many thanks for this. A fascinating installment. (It has been too long since the last one! I tried to send you a direct message on X, but it seems you are no longer there!)