"The Changed Aspect of China"

It's 1890, and Protestant Missionaries Are Conferencing in Shanghai

What were Protestant missionaries in China thinking when my great grandparents, Jimmy and Sophie Graham, were settling into life at Qingjiangpu in the spring of 1890?

It turns out that we have a splendid display of missionary thinking at that very moment. The Shanghai General Missionary Conference met in Shanghai on May 7-20, 1890. And the records of that conference were published in Shanghai before the year’s end.

To one degree or another I have been involved in the publication of many a book of conference papers. And believe me, friends, the publication of the Records of the General Conference of the Protestant Missionaries in China just months later, in late 1890, was an impressive feat! That alone is a quiet testimony to the “enterprise” in the Western Missionary Enterprise. (More on that later.)

The previous general missionary conference had been held in 1877. The 1890 conference was held nearly fifty years after the first opening of the five original Treaty Ports (Treaty of Nanjing, 1842), and thirty years after the Treaty of Peking (1860), which opened the interior of China to Western missionaries.

I have spent many hours reading the papers and responses, browsing the tables and appendices, and generally trying to size up this moment in Protestant missions in China. It deserves much more attention than I will give it here.

The published Records consists of 744 pages—inclusive of a full subject index. It is packed full of papers, responses, tables, and appendices. All of it is historically fascinating.

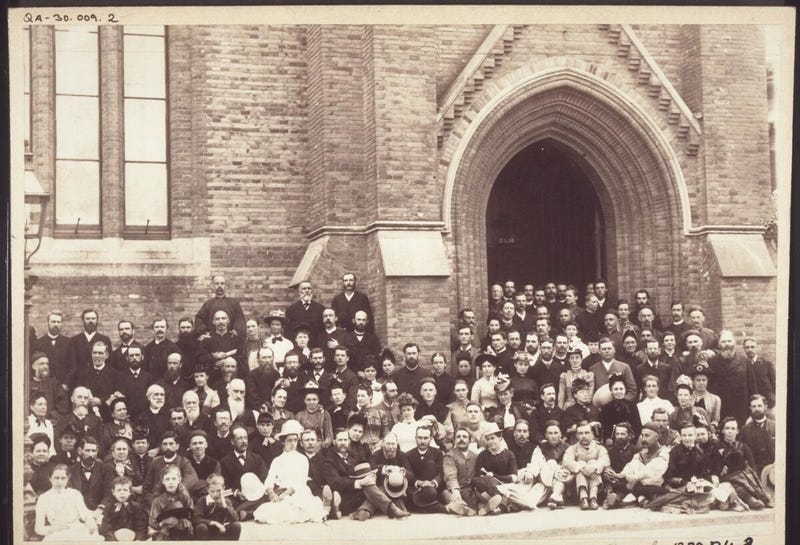

These folks liked to count, tabulate, and analyze. We learn that there were 445 participants, consisting of 233 males and 212 females. While most were from America (180) and Britain (the numbers from each mission organization are tabulated), mission organizations based in Ireland, Sweden, Switzerland and Germany are easily identified as well. The 445 missionaries at the conference represented slightly more than a third of the total 1,296 of China’s Protestant missionaries at that time. The first session was held in Shanghai’s spacious Lyceum Theatre, with subsequent sessions held at the Union Church. And an evening’s social gathering was held on the lawn of the newly completed headquarters of the China Inland Mission.

The greatest representation was from the (British) China Inland Mission (84). Second in number were the American Presbyterians, North, with 49, to which the Southern Presbyterians added 17. The second largest American representation was from the Methodist Episcopal Church at 35, with the Methodist Episcopal Church, South adding an additional 25. Eighteen delegates were not connected with any missionary organization.

The attendees are listed by name, the year of their arrival in China (spanning the years 1847 to 1890), their affiliation, and their location in China. Of course, there were many missionaries who did not, or could not, attend. But we can be sure that the Records of the conference were widely distributed and avidly read.

There is something I always find striking about these nineteenth-century China missionaries: They are not at all shy about viewing their missionary enterprise within the broader advance of Western Christian civilization, or “Christendom.” This was as obvious to them as the superiority of steam power over donkeys, of telegraph over Pony Express.

On the first day of the conference, followng the address of J. Hudson Taylor (an impassioned call for more missionaries), the Rev. Y. J. Allen (D.D., LL.D), of the American Southern Methodist Episcopal Mission, spoke on “The Changed Aspect of China.” Young John Allen (1836-1907) had come to China in 1860, coinciding with the Treaty of Peking and the opening of the interior of China to Western commerce and missionaries. A Southerner from Georgia, Allen had funded his trip to China by selling his land and slaves. By 1890 he was a respected senior missionary.

What was this “Changed Aspect of China”? Fundamentally, it was the opening of China to the West by force. While the circumstances were regrettable, China, which had “mulishly … persisted in cherishing her ignorance, her isolation, her conceit and her folly” (he is quoting a Dr. Williams) had been pried open by Western gunboat diplomacy. From the missionary perspective, this was “not of the will of man altogether” but of the Providence of God.

Henceforth the aspect of China began to be changed. The middle wall of partition1 which had so long separated, as a horizon, between her and foreign nations, was swept away; her exclusiveness was penetrated; her isolation uncovered; her supercilious bearing rebuked; the high prerogatives she had assued were abased, and the hitherto peerless Son of Heaven found himself face to face with a set of new conditions, which however loath to accept, he was compelled to acknowledge and ratify by a treaty which confirmed, (1) to Commerce and Missions, the right of unmolested access to his dominions; (2) to ministers plenipotentiary, the right of residence in his Capital; and (3) to all, the immunities of a jurisdiction extra-territorial.

These terms were severe, and at the time no doubt exceedingly humiliating to China, but they were welcomed abroad, by Church and State, Commerce and Missions, as opening new fields for their enterprise and still greater conquests for our Christian civilization. But as to the extra-territorial clause, in particular, it is doubtful whether either in China or abroad its full significance was at once understood. To the foreigner it meant immunity, to the Chinaman indignity, but neither suspectected the full power of which it was capable. This however was in due time revealed and China was compelled not only to recogize in it the jurisdiction of an imperium in imperio, but to see herself bound over by it unto the tutelage of her Conquerors. In other words, she had accepted conditions from which she could not redeem herself except by a revolution which shall touch every spring of her actions and have for its final outcome the uplifting of the nation to a higher plane of life and civilization. What effect this clause has had and is still having on her conduct will more fully appear hereafter.

Further on, Allen digs deeper:

But lest I be speaking in riddles, it may be well to illustrate fully the place and bearing of this clause in the future conduct of our work.

The conquest of this country in 1860 may be likened to the conquest of primeval America. It gave us access; but as in the one case the luxuriant wild growth of centuries cumbered the earth and must be removed before the settlers could find a home and congenial surroundings, so here were found similar conditions, of a moral character, the elimination of which was necessary to the introduction of that higher civilization so indispensable to the best welfare of mankind. And as in the once case the axe became the pioneer instrument to the possession of what is now fast becoming the greatest nation on the face of the earth, so here the extra-territorial clause is being made the pioneer instrument in the overthrow of what might almost be termed the primeval obstructions in the way of China’s future development.

Well. I cannot say that had I been present at that conference, I would have viewed it differently. But from my perch 134 years later, my eye falls on a book on my shelves entitled Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations (2012). And another, originally published in 1953 by veteran China missionary David M. Paton, Christian Missions and the Judgment of God. Beholding the mysteries of Providence over the long haul (let alone Progress), I am chastened in any perceptions I might have of how things will turn out. And while I think the missionary efforts were right in the main, the cultural attitudes were often deeply problematic. And yet.

And yet the deep structures of the Western critique of China’s culture and imperial hubris would soon be shared to a surprising degree by Chinese intellectuals. It would take hold in the overthrow of the Qing Empire in 1911, it would surge through the 1920s and 1930s and—refashioned on the anvil of Maoist Communism—it would harrow the fields of tradition in the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s. It is a bracing story. And missionaries such as my great grandparents, starting out in late 1889, and living in China until 1940, would be caught up in an epic story that continues to play out to this day.

To be sure, Allen’s address to the conference included more. And we will return to it and supporting, as well as diverging, themes in the conference of 1890.

But I will close with a mishap recorded by the editors of the Report. In an attempt to have a group photograph of the conference attendees, a scaffolding of bamboo was hastily rigged, which would seat the delegates in tiered rows for the photo. Front to back, it rose to a height of eighteen feet. And to be fair, some doubts were expressed about its sturdiness for the task.

When nearly all were seated, the hinder and higher seats began to sway forward on the others, and the whole structure doubled up like a fan, piling men and women, young and old, in one mass at the foot, and catching the feet and legs of a number between the folding timbers. Not a scream was heard, but those who first got on their feet, set to instantly to lift up and drag out those who were piled up, seven or eight deep, before them.

Cuts, bruises, and sprains aside, there were no serious injuries. And the doughty company of missionaries conferenced on, counting it as one more providential deliverance in China.

But from this historical distance, and set in the context of Allen’s address, I can’t help seeing it as an eschatological parable.

I am uncertain whether or not this photo was taken at the 1890 conference, but these missionaries appear to be on solid ground.

The “middle wall of partition” is an allusion to Ephesians 2:14, where the Apostle Paul refers to the Torah, which divided Jew from Gentile and was removed by Christ’s death. It is interesting that Allen finds it a fit image for China’s isolation from Christian civilization.