For much of my youth, I lived, played, and went to school in a place that, in hindsight, had been a nodal point in modern East Asian history. I was not aware of its true significance at the time.

Perhaps those who know me think my youth in Japan was all rice paddies, serene temples, and Hiroshige landscapes. And fast trains. There was some of that. But ours was a poor neighborhood, with a run-down orphanage across our narrow road. Where it lacked charm, however, it offered abandoned bomb-shelter caves for me to explore. And remnants of antiaircraft gun emplacements pockmarking the local landscape beckoned to me.

I went to school in buildings that had formerly housed the Japanese Imperial Navy.1 Five days a week, my school bus rolled past claustrophobic one- and two-man midget submarines, displayed as curiosities from a war only fifteen to twenty years past. I distinctly recall a bomb drill (nuclear, I’m quite sure), in which I filed along with my class into a nearby cave, originally constructed as a shelter from American bombs. And to bracket this whole scene, one train stop or a bike ride away from home, you might find me fishing off the very beach where Commodore Perry, with his “Black Ships,” landed in July 1853 and opened Japan to the West.

Remnants of the Pacific War were all around if you had an eye for them. And that included badly maimed war veterans who were begging on the streets. I somehow acquired a taste for reading accounts of World War 2 prisoner-of-war camps, not realizing there had been one a few stops down the train line. And then there were the ordinary Japanese adults, who stoically bore their inner traumas of the war and carried on.

Ours was a naval town on Tokyo Bay. Still today, it is home to a large and strategic U.S. Navy base. Home of the Seventh Fleet. Fronted and served by “bar alley,” and its “adult entertainment.” (“Welcome USS Midway,” read the banner.) Until August of 1945, it had been an important Japanese Imperial Navy base.

But there were older naval remnants as well. The battleship Mikasa, a proudly preserved relic from the past, was a prominent feature along the shoreline, adjacent to the Navy base. To this day it is a museum and monument to a great and improbable Japanese victory over the Russia in 1905. And there was a shipbuilding industry in town, which seemed as ordinary to me as a bowl of ramen. In the spirit of our town, I recall building a model of the Mikasa.2

I did not fully appreciate how these and other fixtures of my life were rooted in a deeper history, reaching beyond World War 2. In fact, it extended back into the Meiji Restoration, the modernizing of Japan’s Navy, and the restructuring of power in East Asia. Surprisingly, our city’s naval shipbuilding even dated back to 1865 and the Shogunate. With the help of the French, by the 1870s our town had become home to the principal naval shipyard in Japan.

The impressive superstructure of the post-war Pax Americana that I experienced almost daily was in fact mounted atop the formidable skeleton of Japan’s attempt to carve out and colonize a new Asian empire. Euphemistically, it became known as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. A future Pax Japonica, shot through with the ideological propaganda of a superior Yamato Race, ruled by the emperor. (I once saw him in the 1960s, on the beach outside his summer villa, examining the tide pools. In this counterfactual life, he was simply an amateur and published expert on The Crabs of Sagami Bay.3)

History can awaken us to deeper layers lying quietly beneath the commonplace. And the more I have learned and reflected on the place I called home—Yokosuka, Japan—the more I am struck by how we can move through time in the barely permeable envelopes of our lives, not fully comprehending the significance of what surrounds us, or is right beneath our feet. I have sometimes envied the rootedness of those who grew up and lived their lives in a Des Moines or Decatur or Wenatchee. But it does now seem that the ground I trod in my youth held stories of great consequence.

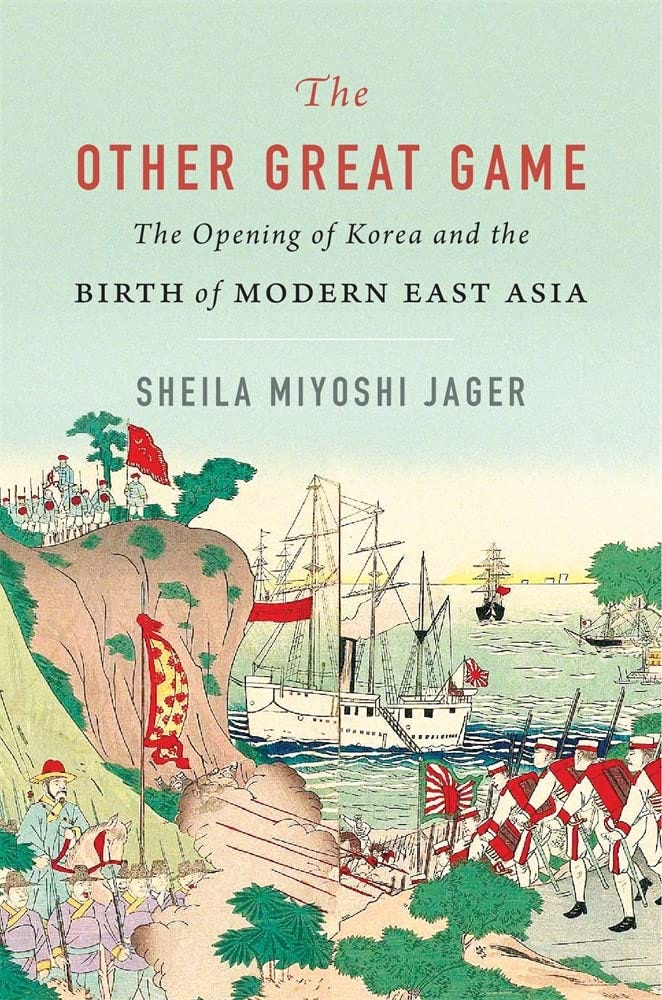

Books such as Ezra Vogel’s China and Japan: Facing History and Sheila Miyoshi Jager’s The Other Great Game: The Opening of Korea and the Birth of Modern East Asia, have sharpened my understanding of how the Pacific War was fundamentally not about “good guys” versus “bad guys,” but about empires.

And so I blithely walked amidst the remains of events that had shaken the world of East Asia and the Pacific. And I had hardly a notion of how my mother’s family in China had watched with keen interest the emergence and momentum of these events.

Rising Empire of the Sun

Scarcely five years into their sojourn in Qingjiangpu, the Grahams were observing the first ripples of change.

In the autumn of 1894, shortly after Jimmy and Sophie Graham had the wind knocked out of them with the death of their little daughter Georgie, a flow of Chinese troops was choking traffic on the Grand Canal. Steam launches arrived bearing men of importance. The city was overridden with officials, soldiers, and munitions, all heading north. Every four or five days soldiers arrived and departed in detachments of 2,000 to 3,000 men. Boatloads of crated arms and ammunition arrived by barge from the south. Some crates were labeled in German, others bore the lettering “Birmingham.”4

The cargo was unloaded, crate by crate, then transferred to hundreds of waiting carts brought down from Tianjin, as well as wheelbarrows. Every donkey cart, every wheelbarrow, and every day-laborer within miles was employed in transporting supplies northward. Henry Woods commented, “On the landing we observed that the coolie hongs adjacent to the mat’on, which are usually noisy and full of coolies offering for hire, were all closed and still as death—not a carrier to be seen.” Wheels squeaked, creaked, and rumbled overland, northward toward Shandong and beyond. And talk on the city streets pulsed with “vague rumours regarding the war.”5

The Southern Presbyterian missionary Henry Woods reported to the North China Herald: “At night the scene . . . is a picturesque one, the many lights of the wagons and carters looking like soldiers’ fires or a gipsy encampment.”6

Absalom Sydenstricker was less charmed. Itinerating over the countryside in his donkey cart, he was accosted by a surly group of Chinese soldiers. After blows and threats, the soldiers abruptly dumped his luggage on the road and made off with his cart and donkey.7

Henry Woods, as he was traveling through the region, had often been asked about his “honorable nationality.” But now there was a further question: How far might his “precious kingdom” be from Japan? Ah, they were reassured to learn, the foreign gentleman came from far over the ocean and nowhere near Japan. But then they were startled to hear that Japan was, in fact, China’s near neighbor. Such were the geographic horizons of most country folk. Their well-worn route from Lower Tiger Village to the Village of Good Fortune did not register on the scale of the Qing’s gazetteer of nations.

But what did these troop movements signify?

Japan was on the move in East Asia. Under the Meiji Restoration, beginning in 1868, Japan had been industrializing and modernizing its society at a rapid clip. Awakened to its vulnerability in the modern world, and not happy to be beholden to Western powers, Japan was keen on remedying its position. And it was taking bold initiatives to learn from Western nations and understand what accounted for their power and success.

In the Iwakura Mission (1871-1873), Japan sent some of its best and brightest on a tour of Western nations to study industry, technology, education, administration, and all things military. Having completed its circuit of Western nations—the U.S., Britain, France, Prussia, Russia—the Iwakura mission stopped in for a brief visit to Shanghai. There, apart from the bustling and impressive International Settlement, they found the once great Middle Kingdom down at the heels, and shockingly innocent of modern progress.

They had been diligent in their study tour, and on their return to Japan the members of the Iwakura mission were placed in key government positions. There they planned and discharged programs of modernization. By the 1880s, Japan’s progress was sharply evident in its army and navy, which had assembled an expanding array of weaponry and war ships.

Already by the 1870s, Japanese had been viewing both Korea and China as inferior nations. And there was a growing opinion that these neighbors were ‘s territories to be subsumed in the interest of a greater “Asia for Asians” policy, led by Japan. What’s more, Russia’s advances in East Asia were alarming. In 1860, in a treaty following the devastating Second Opium War, Russia had acquired 350,000 square miles from China, land bordering northeast China and Korea, including a deep-water port, Vladivostok, “Ruler of the East,” directly across from Japan. The great power of Russia was now a pressing issue for Japan.

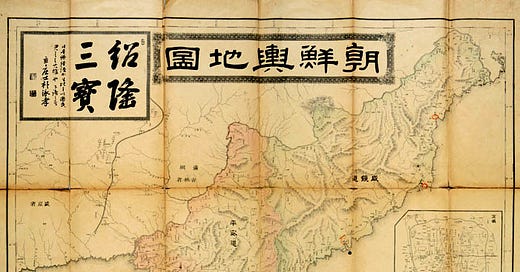

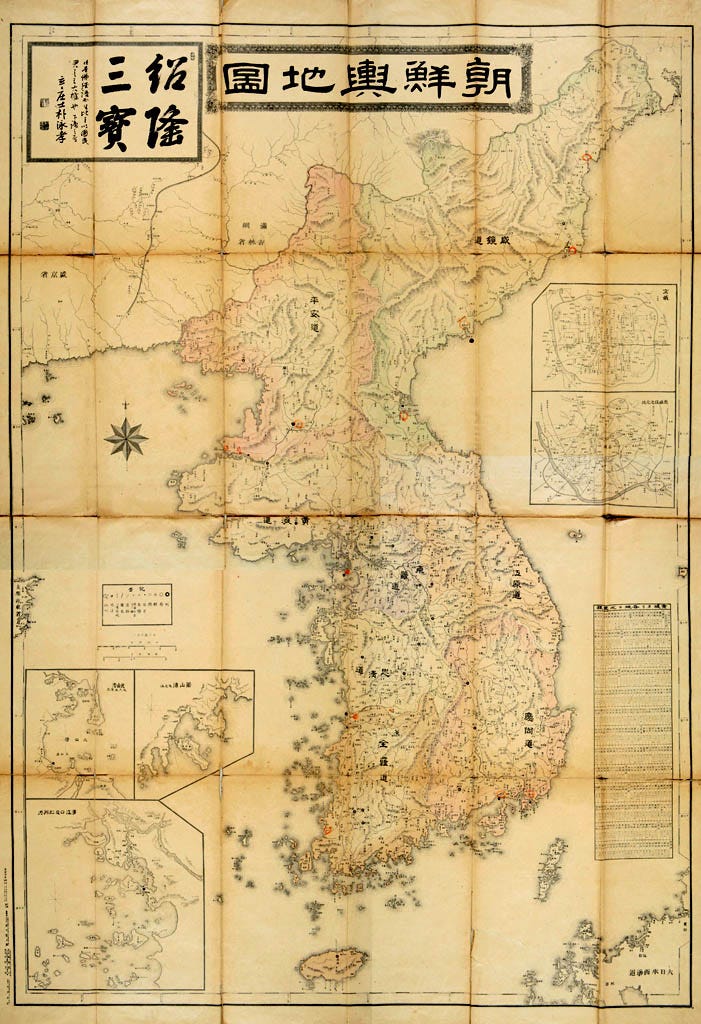

A Japanese Map of Korea from 1894

East Asia’s Great Game is Afoot!

As Sheila Miyoshi Jager tells the story in The Other Great Game, Korea held a critical place in the events that would transpire in East Asia.8 Viewed from China, the Korean peninsula made up “the lips that protect the teeth” of China. As a tributary state of China, it was a buffer across the Yellow Sea to the east. On its northern edge, Korea bordered Manchuria, the homeland of China’s Qing Dynasty. For the Japanese, Korea was a close neighbor across the water, which in 1274 and 1281 had been the platform for two failed attempts of the Mongols to sail across the sea and take Japan. (In both attempts the Mongol ships had been destroyed by a kamikaze, a “divine wind.")

In the late sixteenth century, the Japanese had tried to subjugate the Korean peninsula, with the intention of making it a bridge to conquering Ming China. Despite exacting huge losses and devastation on Korea, the Japanese were driven back with the aid of China. Then, in 1636, the Manchus invaded Korea. And when the Manchus formed the Qing Dynasty in 1644, Korea’s tributary status with China was settled. But Korea remained a “hermit kingdom,” with its isolationist policy warding off foreign intrusion even after China and Japan had been opened up by Western nations.

Cover Art: Kokunimasa Utagawa,9 Victory of Japanese Troops Pursuing Chinese Troops at Asan in Korea (1894)

With China’s Qing Empire weakened with the incursion of Western powers and the unequal treaties, Japan was seeking advantages in Korea and elsewhere. By 1879 Japan had set its eyes on low-hanging fruit, ripe for the plucking. The first was the Ryukyu Islands, the island chain extending south, from the southernmost main Japanese island of Kyushu, toward Taiwan. The islands were loosely tributaries to China, but an opportunity opened, and the fruit was plucked and annexed for Japan. The largest island in the chain was Okinawa.

When in 1894 Japan was prepared to further expand its imperial power, the Qing government was unprepared. While Japan had accumulated a great deal of intelligence on China, Chinese leadership had exhibited little curiosity toward Japan. In fact, the imperial leadership in Beijing seemed more taken up with preparations for the sixtieth birthday celebration of the empress dowager.10 And the general thinking in China was that little Japan, historically home to the “dwarf bandits,” was not a serious threat to the broad-shouldered Middle Kingdom.

But as an island nation, Japan had seized on the principle that sea power was the key to extending its reach and turning the course of East Asian history.11 China, despite its ancient pedigree as a seagoing empire, had lost its maritime strength.

An opportunity opened in 1894. With a domestic uprising in Korea, the Korean king found himself in a precarious position. Both China and Japan made self-interested bids to put down the uprising, but it was resolved without their intervention. However, Japan was looking for a pretext to go to war with China. And through nimble manipulations and palace intrigue, on July 23 they installed a regent of their own choosing in the palace at Seoul.

Conflict with China immediately ensued. On the Yellow Sea, Chinese troops aboard a leased British transport ship were attacked by the Japanese, and the ship was sunk on July 25. There followed land battles, in which the Chinese were defeated near Seoul and Pyongyang. In October the Japanese pressed north through the Korean peninsula, and on October 24 they crossed the Yalu River, the border between Korea and Manchuria.

The Japanese were now in Qing territory, and they pressed on to take Port Arthur (present-day Lushun). There Japanese soldiers, enraged at finding Japanese heads on stakes, unleashed brutal atrocities on the civilian population. Then, having thoroughly defeated the Chinese navy off the mouth of the Yalu River, they crossed the Yellow Sea to China’s mainland. And in January 1895 they took the fortified port of Weihai, at the tip of China’s Shandong Peninsula. Having seized the Chinese forts on the coast, they proceeded to shell the Chinese navy from its own shore and destroyed one battleship and four cruisers.

The effect was devastating. And the defeat was testimony to the discipline, tactics, and dedication to sea power of the Japanese armed forces.12 To this day it is remembered as a searing episode in China’s long memory of its “century of humiliation.” However, at the time the victory was much celebrated in Japan as the end of its own centuries of humiliation by China.

The outcome was settled in the Treaty of Shimonoseki in April 1895. It was negotiated on Japanese soil, while Japanese troops were positioned within marching distance of Beijing. The treaty granted the independence and autonomy of Korea from Chinese suzerainty, but with the effect that it became a protectorate of Japan. In addition to an indemnity of 200 million taels paid to Japan, the Qing also ceded to Japan the island of Taiwan, the Pescadores, and a region of southern Manchuria.

What’s more, the Japanese were granted four more treaty ports in China, including Chongqing, far up the Yangtze River. They were also granted the right to build factories in treaty ports. Overall, the loss and shame for the Qing was staggering. Japan had now fully entered the company of the Western treaty-port powers. And the colonizing power of imperial Japan would become a growing reality in East Asia and beyond for the next half century.13

Back in Qingjiangpu, as spring had melted into the hot summer of 1895, troops and munitions continued to pass through the town. But the bigger picture was often shrouded in ambiguity. Straw houses were being torn down as earthworks around the city suburbs were being built up as a defense, with cast iron canons mounted atop, perhaps as dummy defenses. Raw recruits were drilled in a shambolic version of “Western-style” military marching, offering hilarious entertainment for spectators. And a fire that left forty-six families homeless came perilously close to a temple in which gunpowder and ammunition were stored. In some sort of propitiatory rite, an official threw his boots into the fire.14

By July the troops encamped in the area were growing restless over not having been paid, even though silver ingots were being shipped through the town to pay troops to the north. In Qingjiangpu and Huai’an, cholera broke out and lives were lost. When 150 cavalry and 1,500 infantrymen entered the city and converged on the yamen, demanding payment, they were driven back. Frightened officials sent anxious telegrams crackling through the lines to the viceroy in Nanjing. The matter was settled with a promise of one-month’s pay now and the remainder upon the troops’ return home—lest the soldiers decide to prolong their stay and become a persistent nuisance.15

Such was the unfolding of these consequential events as viewed from a provincial city on the Grand Canal. Fragmented. Haphazard. Mystifying. The handful of Western missionaries in Qingjiangpu took great interest in these developments, garnering whatever reliable information they could on the ground, and awaiting the slow-boat arrival of the North China Herald from Shanghai to put things in context.

But they noted how little interest the average Chinese took in the war or understood its potential consequences. It seemed that, to the provincial mind, the bounty of the harvests and the local market rate for grain was of far greater moment than events in far off Beijing or Tokyo.16

The Long Memory of Humiliation

The Treaty of Shimonoseki would send shock waves through China. And the memory endures.

In August of 2014, a group of naval personnel gathered at Weihai to remember the defeat of 1895, a marker in China’s “century of humiliation.” Daniel Yergin recounts Admiral Wu Shengli’s address that day:

“History reminds us that a country will not prosper without maritime power,” Wu said. The century of humiliation, he argued, was the result of insufficient naval strength, which the Weihai defeat had demonstrated. But today, “the sea is no obstacle; the history of national humiliation is gone, never to return.”17

The serious implications for Taiwan and East Asia today should be plain enough. But with a new U.S. administration soon to take its seat in 2025, one wonders whether this will have any effect on the transactional pragmatics of “America First.”

The Great Game continues.

A word of explanation: My parents were missionaries, but I was able to attend a Department of Defense school on the U.S. Navy base a couple miles from our house. So every school day—and often more than that—I visited “America,” and even had a coveted pass to enter the base for other activities.

Though the Mikasa itself, Wikipedia informs me, was British built, and paid for by the colossal indemnity inflicted on China after Japan’s victory in the first Sino-Japanese War of 1895. As we will see, these things are not forgiven and forgotten in East Asia.

You think I’m kidding, don’t you. Look it up!

North China Herald (NCH) (January 25, 1895), 117.

NCH (November 2, 1894), 729.

NCH (January 25, 1895), 117.

NCH (December 7, 1894), 931.

Shiela Miyoshi Jager, The Other Great Game: The Opening of Korea and the Birth of Modern East Asia, (Harvard University Press, 2023) See also https://lawliberty.org/book-review/the-race-for-asian-hegemony/. The “Great Game,” for which the struggle over Korea is the counterpart, is the late-nineteenth-century struggle for influence in Central Asia between Britain and Russia, which ended in 1907. See Peter Hopkirk, The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia (Kodansha, 1992).

If you search for the artist’s name, you will find numerous examples of his renderings of battle scenes of the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-1895.

Henry Woods reported that the local Qing official, the Daotai, “has gotten into trouble and been cashiered. The Chinese put it facetiously: He has been ‘invited to Peking to attend the festivities in honour of the Empress Dowager.’” NCH, November 2, 1894.

Alfred Thayer Mahan’s influential book, The Influence of Sea Power on History (1890), was early translated into Japanese and used as a textbook in the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Miyoshi Jager, The Other Great Game, Chapter Seven, tells the story in detail.

Ezra F. Vogel, China and Japan, pp. 132-33. The Treaty of Shimonoseki would not be ended until 1946.

NCH (June 7, 1895), 867.

NCH (July 26, 1895), 143.

NCH (January 25, 1895), 117.

Daniel Yergin, “The World’s Most Important Body of Water,” The Atlantic (December 15, 2020).

A fascinating description of the cultural differences, visionary concepts of empire, and the cultural rifts that have their roots over 150 years ago!