China Between Two Visions

"Who Could Withstand the Mighty Draw of History, Letters, Roads, and Laws?"

If a Westerner had wished to observe a great civilization in epochal transition, there was no better time and place to begin than China at the end of the nineteenth century. Arriving about 1890, you would have enough time to gain a working knowledge of the language and culture. Then, in short order, critical events would begin to unfold. Extending your stay to, say, 1940, and thus avoiding the unpleasantness of a Japanese prison camp, the arc of China’s entry into the modern world could be experienced first hand. There had been critical episodes in the run up to this period, but they wouldn’t fit into one lifetime. And besides, you could master those events by study, inquiry, and observation.

This was the crucible of history which Sophie and Jimmy Graham entered, and lived, and moved, and had their being for fifty years. “Short-term” was not in their vocabulary. But they had no notion of taking a ringside seat to watch China go through the epochal transition that it did. They had something else in mind.

“Put Your Hand on the Springs That Shape the Destiny of Nations.”

Sophie and Jimmy Graham’s generation of Christian young people was animated by figures such as the Presbyterian pastor A. T. Pierson, and his call to “evangelize the world in this generation.”

In fact, Jimmy Graham had heard A. T. Pierson address the annual conference of the American Inter-Seminary Missionary Alliance in October 1887, at Christ Church (Episcopal) in Alexandria, Virginia.1 He, along with other students from Union Seminary (Virginia), had mingled with students (all male, of course) from Princeton, McCormick, Yale, Harvard, Union (New York), Crozer, Andover, Oberlin and numerous other seminaries and divinity schools.2 Jimmy seems to have been deeply involved in the Alliance, and was on the conference’s Committee on Resolutions.3

What is easily lost on Americans today—whether of Christian or other faith, or non-religious—is that this was not a sectarian movement operating in a cultural corner of society. It was supported across the Protestant denominations, which in turn had wide societal draw and influence. Notably, on the concluding day of the 1887 conference, a telegram was received from President Cleveland, inviting the conference delegates to a reception on the following day at the White House.4

As Pierson liked to point out, he was drawing upon the best of young people, from the best of schools, and inspiring them with a grand vision into which they could direct their energies, talents, and lives. To the seminary students gathered in Alexandria in 1887, he said:

“Think what you may see before you die, whole empires turned to Christ, systems honeycomed [sic] by the gospel, the whole world, perhaps, permeated by the leaven of God’s truth. You can put your hand on the springs that shape the destiny of nations.”5

In his widely-read book The Crisis of Missions (1886),6 Pierson painted a picture of a China now open to the gospel:

On August 25 of that memorable year [1858] the Atlantic cable shot across the ocean-bed the news that this colossal Oriental empire was open not only to the commerce of the world, but to the gospel.

The pride of the Chinese in their ancient civilization and religious and ethical faiths presented a formidable barrier to evangelization. Their national isolation is partly the result of inordinate conceit. The Emperor is the Son of Heaven, sits on a dragon throne, signs decrees with a vermilion pencil; his empire is the “middle kingdom,” his people the “celestials.” The geography of the Chinese gave nine tenths of the globe to China, a square inch to England, and left out America altogether. … Yet their “golden age” is manifestly past, and for centuries they have halted and made no progress, ever resisting innovation. But as they begin to feel the power of contact and intercourse with enlightened nations, the petrified constitution and culture of four thousand years begins to lose its impenetrability and inflexibility. … As Carleton Coffin prophesied years ago, the superstition about the “Earth Dragon” will be exploded when the Chinaman sees the railway ploughing through even the burial-places of his ancestors. Geomancy must die before modern civilization, and the gospel will take its place.7

The triumphalism of an assured Providence carries on in this vein. In the Treaty of Tientsin, the Great Wall had come down and—after an allusion to Israel entering and taking possession of the land—we read: “To all the provinces, with their seventeen hundred cities and innumerable villages, the missionary may go, without hindrance or molestation; claiming in case of necessity protection and aid…. That door was opened not by the vermilion pencil of the Emperor, but by the decree of the Eternal.” The veteran China missionary Dr. Williams reportedly “thinks that half a century or more of Christian missions will evangelize, and even Christianize, the empire.” The Chinese, “these Oriental Yankees, once brought to Christ, will become the aggressive missionary race of the Orient.”8

To read Pierson is to enter into an extraordinary view of Providence casting open the global gates of nations to Protestant missions. His rhetoric soars. “India is now a starry firmament, sparkling with mission stations.” “Japan strides in her ‘seven league boots’ toward a Christian civilization, and with a rapidity that rivals apostolic days.” “Polynesia’s thousand church-spires point like fingers to the sky, and where the cannibal ovens roasted the victims for the feast of death, the Lord’s table is now spread for the feast of life and love.”9 Beneath this flow of arresting imagery is a cultural moment of Protestant perception. The world was at an extraordinary turning point, and the “crisis of missions” was a lethargic Christian response to seizing the moment. Pierson aimed to set young people on fire with a passion to rise to the great challenge of the hour.

But for missionaries on the ground, keeping their eyes on Pierson’s grand narrative arc would prove difficult in real time. At any moment they were presented with conflicting and tangled story lines, not to speak of hostile resistance. And even those who by conviction viewed the narrative through-line of Providence on a somewhat modified scale—perhaps over the longue durée of post-millenialism10—were often buffeted in the near term. Those who were captured by Isaiah’s vision of the nations streaming toward Zion in the last days were encountering the emergence of alternative visions in East Asia.

The imperial order the Grahams had entered in December of 1889 was the Qing Dynasty, which had ruled over the Middle Kingdom since 1644. The Qing emperors were Manchus, from Manchuria, not Han Chinese. But they had run an efficient imperial bureaucracy for most of their 250 years. They had skillfully grafted their rule onto the ancient Mandate of Heaven. They had adopted the structures of Confucian legitimacy. They had taken on the trappings of the ancient dynasties of China. And in an imagined counterfactual reality, where Western nations had not arrived at the gates of the Empire, had not shaken the pillars upholding the celestial canopy, things might have continued for yet some time.

But the weakness of the Qing was becoming evident, and not only to Westerners. As we have already seen, throughout most of the nineteenth century, internal and external forces had conspired against the Qing imperium, carving away at its decaying edifice of power, and forcing China into the modern world.

The World Viewed from the Dragon Throne

Harmony accumulates, bright prosperity is rebuilt,

Imperial tributaries pay homage from all directions.

Who could withstand the mighty draw of history, letters, roads, and laws?

…

How vast, how extensive is the outline of our current domains!11

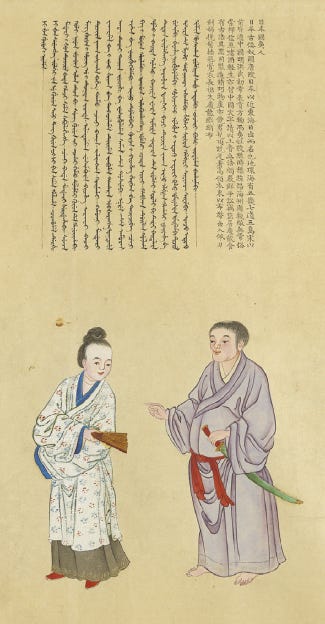

We capture the vision of the reach and splendor of the Qing Empire in a magnificent work called Huang Qing Zhigong Tu, or “Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples.”12 Published sometime after 1759, under the auspices of the throne, it sets out in four scrolls of sumptuous cartographic display the peoples over whom the universal empire of the Qing extended (tribes of various provinces), and beyond (borderlands, Central Asia, and other categories, including notable Atlantic nations). The text is in two parallel columns of beautifully written Manchu and Chinese script, and is now translated into English. The peoples are each rendered, male and female, in lavish color and costume, with their peculiarities of dress and habit described. (I can scarcely do it justice here.)

Here was a projection of the glory of the Qing Empire, an ideological tour de force portraying the diverse peoples whose fealty (in fact or in ideological vision) orbited the imperial throne. But the vision also extended into the outer rings of barbarism, even to the meddlesome nations of the Atlantic.13

From the seat of the Qing Empire, the lands bordering the Atlantic abounded with curiosities. We learn that the people of Holland, during the Ming Dynasty, “often rode in big war vessels, which they anchored in Xiangshan harbor. They requested a trading relationship with China, but it did not happen. Therefore, they entered Fujian and took possession of Penghu and encroached upon Taiwan’s land.” “They can be further subdivided according to the names Swedish and English.”14

“England is a tributary of Holland. The clothing and ornaments of their people are similar. The country is rather wealthy. Men mostly wear woolens and are fond of drinking. Women bind their waists before marriage, desiring them to be thin…. They use a golden thread for their stash of snuff, which they keep on their person.”15

The Portuguese. Ah, the Portuguese! “Without permission, they entered Xiangshan’s Macao…. Their men are strong, fierce, and versed in weaponry. They have repeatedly taken Malacca and Luzon by storm and have divided the Moluccan Islands equally with the Dutch. On their own, without authority, they exhaust the profits of the coastal areas near Fujian and Guangdong. At first they followed Buddhism and later Christianity…. These foreigners wear white kerchiefs on their heads and also black-felt caps. They take off their hats to be polite.”16

Much closer to home are the inhabitants of Jianpuzhai (Cambodia): “By nature the people are meek. They are good at raising elephants.” While in the northeastern borderlands, “the Qixing are located in Wuzhalahongke more than 200 li west of Sanxing…. During the hard freeze of the winter months they wear wooden snowshoes when they hunt. Their women are also good at using a crossbow to hunt martens.”

And there is more, much much more.

But if we had been reading this Qing guide to peoples and nations in the late nineteenth century, one hundred years after its publication, we would have found its perspective strikingly at odds with the events that were now unfolding and would resound over the decades to follow.

Three examples stand out.

Of the Ryukyu Islands, that extend south from Japan’s island of Kyushu, toward Taiwan, we read:

“Under the stability of the Qing dynasty, Ryukyu’s kings sailed the seas and remained submissive. Envoys were sent to invest them with rank. The emperor gave them a wooden placard inscribed in his own handwriting. Officials often bring their children to China to study.”17

Of Taiwan:

“From ancient times Taiwan did not have contact with China. It came onto the map for the first time during the Qing dynasty.” “Annually they submit more than 70 liang of head tax.”18

And of Japan:

“In ancient times, Japan was the country of Wonu [“dwarf slaves”]. In the Tang dynasty the name changed to Japan, Riben. It was so named because it was close to where the sun rises over the eastern sea. Its land is surrounded by sea.” Its “people are crafty and cunning by nature.” Of the men, “Coming and going they wear a knife and sword at their waist.”19

The classic view of the world from the Dragon Throne was that the tribes of the earth flowed from north, south, east, and west, bearing their tribute, to bow before the imperial glory of the Great Qing.

But startling change was underway in East Asia. And if it would eventually challenge the vision of an A. T. Pierson, it would first overthrow the settled confidence represented in the Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples.20

And the revolutionary new world that was dawning was soon casting its rays on some of China’s young people. In 1912, shortly after the fall of the Qing Empire, a young man of nineteen, from a village in the southern province of Hunan, saw a modern map of the world for his first time. And he was astounded. How could it be that the Middle Kingdom, as large as it was, had occupied so little space amidst the vast sprawl of nations?

The lad’s name was Mao Zedong.21

Next up, it’s 1894-1895, and the Southern Presbyterian missionaries in Qingjiangpu are noting the rippling effects of a new shock wave hitting the Celestial Kingdom.

Here I gladly tip my hat to Michael Hamilton, a friend and historian of American religion, who reminded me of A. T. Pierson’s influence in that era and loaned me his copy of Dana L. Robert’s valuable study, Occupy Until I Come: A. T. Pierson and the Evangelization of the World (Eerdmans, 2003). That led me to investigate the Inter-Seminary Missionary Alliance, and then to stumble onto the delightful discovery of Jimmy Graham’s involvement with the Alliance. This confirmed what I’d long suspected: that among scholars of religion, American historians enjoy a disproportionate amount of research gratification.

The conference program, papers, proceedings, and lists of participants are laid out in the Report of the Eighth Annual Convention of the American Inter-Seminary Missionary Alliance. Alexandria, VA. October 27th, 28th, 29th and 30th, 1887 (Chicago: Kittredge & Friott, 1888). There were 237 delegates in attendance, from 39 institutions. Sixty-four delegates signed the pledge: “We are willing and desirous, God permitting, to be foreign missionaries”

The committee set forth a resolution urging the Bureau of Indian Affairs to reconsider its recent policy prohibiting “the use of native tongues in all Indian schools,” and excluding the use of the Indian Bible in all mission schools. They appealed to the commissioner that this order not apply to mission schools that were independent of government support. It is interesting that Jimmy Graham had an uncle, the Confederate veteran Capt. William L. Powell (married to Ann Evilina Hunter Magill, 1832-1901), who was Indian Agent for the Makah tribe at Neah Bay, Washington (where he died in May 1895). This is at the far northwestern tip of Washington State. Powell’s reports evince an admiration and confidence in the Makah’s self-sufficiency from the produce of the sea and from trade.

I had missed this in my earlier reading of the proceedings of the conference. But it punctuates the point of my previous post on missionary diplomacy.

Report of the Eighth Annual Convention, 54.

Arthur T. Pierson, The Crisis of Missions; or, The Voice Out of the Cloud (London: James Nisbet, 1886). This was a best-selling book on missions, one that both Sophie and Jimmy Graham would have read. The digital copy I am citing was from “The Missionary Library” of the University of Virginia, presented by the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), as a gift of a certain Lindsay C. Marshall, December 25, 1896. This in itself is one of many indicators of the cultural footprint of the Christian missionary movement in that era.

Pierson, Crisis, 83-85.

Pierson, Crisis, 93-94.

Pierson, Crisis, 41-42. When Pierson speaks of Japan, he is giving rhetorical gloss to a view expressed by some missionaries on the ground. There was a surge of interest in Christianity, such that one predicted the end of “foreign missions” in Japan by the turn of the century.

The Christian eschatological view that Christ would return after his kingdom had been established on earth. This was a common view among Protestants in the nineteenth century. And it would have been a common view among the Presbyterian missionaries we have been following, though viewpoints began to shift, particularly in the early twentieth century. In an early post I noted that the Southern Presbyterian missionary Hampden DuBose exemplified a long view of the effect of missions in China.

From the Prefatory Poem of the Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples.

Laura Hostetler and Xuemei Wu, eds., Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples (Huang Qing zhigong tu): A Cultural Cartography of Empire (Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic and Central Asian Studies, Volume 29; Brill, 2022), 671 pages.

Hostetler and Wu, Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples, p. 5.

Hostetler and Wu, Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples, 85.

Hostetler and Wu, Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples, 71.

Hostetler and Wu, Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples, 73.

Hostetler and Wu, Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples, 35.

Hostetler and Wu, Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples, 195.

Hostetler and Wu, Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributary Peoples, 77.

Though it would seem that an update of the Qing vision is alive in the heart of Xi Jinping today.

Alexander V. Pantsov with Steven I. Levine, Mao: The Real Story (Simon & Schuster, 2012), 36.