Of Canonical Texts and Cultural Contexts

And the Making of “The Greatest Revolution the World Has Yet Seen.”

We continue our exploration of the rise of the “Heavenly Kingdom” of the Taiping. The previous entry focused on the missionary James Legge. Today we begin again with Legge in our transition to Hong Xiuquan, the future Heavenly King of the Taiping.

Hong Kong, 1843.

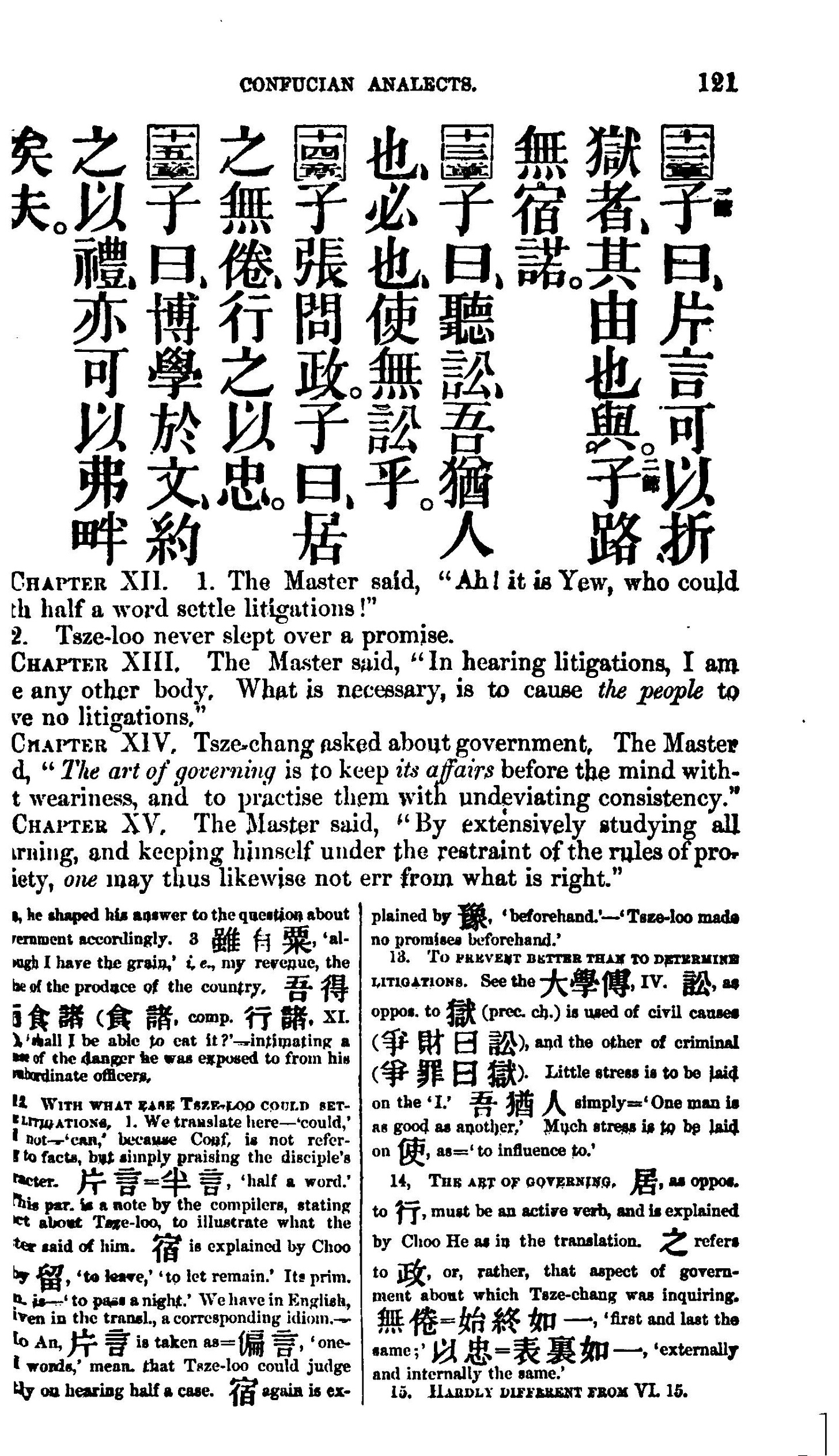

James Legge rises at three a.m.—as is his habit—before the household stirs. He boils his tea water, and sits down to study and translate the Confucian classics. By the flickering light of his lamp, he is groping for the meaning of these texts. He leans in and hovers over the gulf between his Scottish realism and the far horizon of ancient Confucian tradition. He persists by mental discipline and a conviction that this work is integral to his missionary calling.

Some 160 years after he published “The Analects” of Confucius (1860), Legge’s work still stands. Its edges may be nibbled by critical scholarship. But still, it can be said today that “his thoughtful and erudite translation has not been superseded.”1

That same morning Legge will no doubt be poring over the familiar Greek text of the New Testament. Much of it he has memorized, a habitual practice of a missionary scholar. He is sipping its devotional nectar, his palate refined by a great Western tradition. His biblical interpretation runs in historically well marked channels. He drinks from long-hallowed wells.

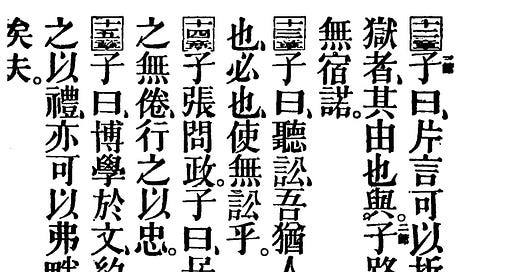

A page from James Legge’s translation of the Analects of Confucius

Guangzhou (Canton), 1843.

Hong Xiuquan sits in a dank, cramped examination cell. He is one of thousands ensconced in the sprawling regional examination hall. Writing brushes, ink stick, ink slab, and paper are his tools. A stocked mind his arsenal. He has brought with him the bare necessities of lamp, food, water, bedding, and chamber pot. For three days and two nights, in strict isolation, he crafts exacting answers to questions. He may not err by a jot or tittle in his recall of the canonical texts. The excruciating tension is followed by the days of waiting for the exam results to be posted. He is making his fourth attempt to pass the imperial examination, and on this his future hangs by a thread.

Hong Xiuquan is twenty-nine years old, scarcely a year older than James Legge. For years he has been studying, memorizing, imbibing the great texts of the Confucian tradition. He has practiced his writing of the prescribed eight-legged essays. He has been formed in a society and culture shaped by these texts. Its ancient heritage is for him a living tradition, imbibed from his mother’s breast, instilled by his father’s discipline, drilled in classroom recitations. Its precepts flow in the streets and alleyways of his town. From family to school, from marketplace to government centers, it is the operating system2 behind the visible screen of social interactions. When Hong Xiuquan opens a Confucian text, he is taking part in the great conversation of the centuries, where even the subtlest sayings of Confucius or Mencius has found a plausible consensus of meaning.

But once again, for a fourth time, he fails to pass the exam.

The ambitious striving, the strain, the anxiety had already taken a toll on Hong Xiuquan. In 1837, after his third attempt, and another failure to pass, Hong had collapsed. The pressure of social expectations, and the shame of repeated failures were too much. There followed weeks in which, bed-bound and convalescing, he had a dream or vision that would prove formative for his future. In the vision he is transported to heaven in a sedan chair. There he meets a heavenly father figure with a long golden beard, and an elder son, and he engages in combat with demons, who are led by the king of hell.3

In addition to his great disappointments, Hong Xiuquan was surely sensing epochal changes in the air. Jonathan Spence speaks of the “aura” and “overlapping layers of change” that Westerners were bringing to China, with their commerce and technology. And the events surrounding the “opium war” of 1842 were an explosive disruption in Canton. And, of course, there were the Western emissaries of Christianity, a new religious teaching that seemed vitally attached to these cultural and social upheavals. This and more amounted to “an aura that was dense enough to give Hong a range of new feelings about the religious and social beliefs he had absorbed at home as a child.”4

Something of that aura also lingered over Liang Fa’s “Good Words for Exhorting the Age.” This was a book Hong had received from the hand of a Western missionary, who was distributing copies to examinees in 1836. The free distribution of “morality books”—the genre in which Liang’s work best fits—was a common scene at examination venues. Typically these books presented a morality situated in a matrix of Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist virtues and encouraged good behavior and a moral leavening of society.5 Hong Xiuquan had put the book away and did not read it.

But in the summer of 1843, Hong Xiuquan did read Liang’s “Good Words,” which had been in his possession for several years. And it was a turning point.

Liang Fa (1789-1855), a convert of Robert Morrison’s, was one of the first Chinese Protestant converts (baptized 1816).6 Liang had entered the trade of carving wooden printing blocks. This had in turn led to his association with the missionaries Morrison and William Milne in printing Bibles and tracts. In time he was converted to Christian faith. And in 1823 Morrison appointed him a “native evangelist” of the London Missionary Society, and a few years later as the first Chinese pastor. In 1832 Liang produced his own nine-part book Quanshi liangyan, “Good Words for Exhorting the Age.”

In some 500 pages, this work included numerous texts from a Chinese Bible translation (by Morrison & Milne) as well as instruction in biblical themes, such as Noah and the Flood, the Ten Commandments, redemption in Christ, the Sermon on the Mount, and select themes from the Apostle Paul’s letters. Significantly for Hong Xiuquan, Liang told of the High God in heaven sending his Holy Son to be born of a woman. That momentous event had been heralded by an army of angels declaring, “Glory to God in heaven, and on earth Great Peace [Taiping], and good will toward men.” Here was a note that resonated in Hong Xiuquan’s heart.

So within months of failing in his fourth examination attempt, Hong Xiuquan was encountering the biblical texts of Legge’s grounding. But he would bring to his reading an entirely different interpretive lens from that of Legge and other missionaries. And remarkably, as things ran their course, the sacred canopy of the imperial heavens would tremble and verge on collapse under his leadership of the Taiping uprising.

On any given morning I will read pieces in the New York Times—often in the “Opinion” section. The attempts to size up national and world developments fascinate me, but as much for their latent—yet undisclosed, but inevitable—failures as by their brilliance.

As we have seen earlier (link below), by the early 1850s Hong Xiuquan’s “Heavenly Kingdom” was beginning to catch the attention of Westerners in China and beyond.

The Abiding Strangeness of the Past

In Why Study the Past? Rowan Williams comments on writing history as a balancing act of “concern with difference and concern with continuity.” As he puts it: “the risk of not acknowledging the strangeness of the past is as great as treating it as purely and simply a foreign country.”

And now in the Western press, the chatterers did chatter:

June 14, 1853. Karl Marx, writing for the New-York Daily Tribune, sees it as a long-brewing class struggle and revolution.

April 8, 1853 (quoting from the North China Mail). The London Times speculates that this might be the revolution that China needed. And by the end of August the Times submits that the uprising is “in all respects the greatest revolution the world has yet seen.”

May 22, 1853. The New Orleans Daily Picayune views it as a revolt of a formerly submissive underclass against their Manchu overlords. And in this there lies a lesson and a warning for the Southern master class, who are lulled into thinking that the peaceful and ordered coexistence of masters and slaves in the American South is safe from a similar collapse.7

Even today, in the Chinese Communist Party’s approved revisionist history, the religious motivations of the Taiping uprising are screened out, and it is viewed as a precursor to the Communist revolution.

And one hundred and sixty years after the events, academic historians are still taking the full measure of the Taiping Civil War.8

And so, of course, I too will attempt to say more….

Moss Roberts, trans., The Analects: Conclusions and Conversations of Confucius (University of California Press, 2020), 10.

I owe the analogy to Roberts, Analects, 3.

Jonathan D. Spence, God’s Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan (Norton, 1996) , 46-49.

Spence, God’s Chinese Son, xxvi.

Zexi (Jesse) Sun, “Translating the Christian Moral Message: Reading Liang Fa’s Good Words to Admonish the Age in the Tradition of Morality Books,” Studies in World Christianity 24.2 (2018): 101.

For a summary, see P. Richard Bohr, “Liang Fa: Pioneer Chinese Protestant Evangelist,” Studies in World Christianity 27.3 (2021): 253–279; George Hunter McNeur, Liang A-Fa: China’s First Preacher, 1789-1855, introduced and edited by Jonathan A. Seitz (Pickwick Publications, 2013 [1934]).

These news items are related in Stephen R. Platt, Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom (Vintage, 2012), 10-12. For a wide selection of Western reports, see Prescott Clarke and J. S. Gregory, Western Reports on the Taiping: A Selection of Documents (Australian National University Press, 1982).

Earlier I mentioned the latest entry: Huan Jin, The Collapse of Heaven: The Taiping Civil War and Chinese Literature and Culture, 1850-1880 (Harvard University Press, 2024).