Among the nineteenth-century Western missionaries to China, James Legge is a standout. In my previous post I introduced the Taiping uprising. My mention of James Legge led me into an Easter weekend preoccupation with his work and its implications. I find him intriguing in his own right, but also as an important intersection between Western missionaries and the Taiping uprising. So we pause our Taiping story for a bit of James Legge.

James Legge1 had arrived in Hong Kong in 1843 as head of the Anglo-Chinese College, a theological school that had been relocated from Malacca, Malaya. Legge was a Scottish Congregationalist and a missionary with the London Missionary Society. He would spend over thirty years (1840-1873) in distinguished missionary service to the Chinese, amidst numerous difficulties.

Legge is an outstanding example of those early missionaries who combined scholarship with evangelism. His practice was to rise at three a.m. and work on Chinese texts, and his labors eventually led to his appointment as the first professor of Chinese at Oxford University (1876-1897). Legge would achieve an international reputation for his five-volume translation of the Chinese Classics, which is still highly regarded today.

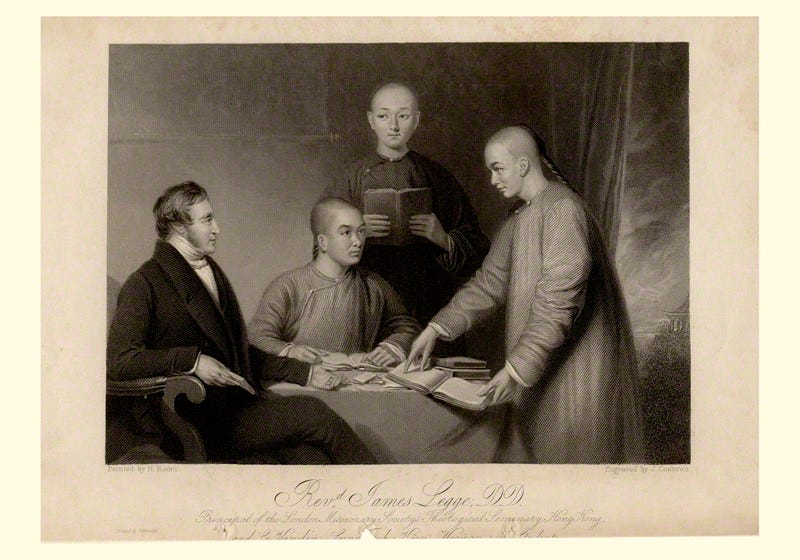

James Legge with his Chinese assistants

Legge had high regard for Hong Rengan, the cousin of Hong Xiuquan, the Taiping leader (see previous post on “The Abiding Strangeness of the Past”). Legge had employed Hong Rengan as a trusted catechist and preacher, as well as an assistant in his scholarly research. Their mutual friendship and respect seems to have been strong in those days. And years later Legge would reflect back on Hong as “the most genial and versatile Chinese I have ever known, and of whom I can never think but with esteem and regret.”2

Legge had long wrestled with the question of how to render the biblical deity in Chinese (the so-called term question). Legge was a proponent of using Shangdi, the “High God.” In Legge’s view, the biblical figure of Melchizedek, who Genesis 14 portrays as “king of Salem” and a “priest of the Most High God” presented a striking analogy to China’s religious tradition. Legge maintained that Christian Scripture strongly affirmed the possibility of God’s leaving witnesses to himself, however much they may have been corrupted or distorted over time.3

It was Legge’s deep study of Confucian texts that convinced him that there had been in China an ancient understanding and worship of a Most High God, which could be used as a bridge to Christian revelation.4 Arguably, his translation of the Chinese classics was in part motivated by his desire to demonstrate the suitability of using Shangdi for the God of the Bible.5 It seems very likely that Legge would have discussed this with Hong Rengan.

Legge’s work with the Chinese classics also led him to an important hermeneutical insight. The classic texts should not be interpreted at a “literalistic” face value. The Chinese characters were not a transcription of what the authors would “say.” They are windows into what the authors think. As Legge explained it:

It is vain … for a translator to attempt a literal version. When the symbolic characters have brought his mind en rapport with that of his author, he is free to render the ideas in his own or any other speech in the best manner that he can attain to. This is the rule which Mencius followed in interpreting the old poems of his country: – “We must try with our thoughts to meet the scope of a sentence, and then we shall apprehend it.” In the study of a Chinese classical book there is not so much an interpretation of the characters employed by the writer as a participation of his thoughts; – there is the seeing of mind to mind.6

This is a fascinating insight into the interpretation of classic Chinese texts, which Legge stumbled upon in his wrestling with their interpretation. And it runs against the grain of the Scottish “common sense” interpretive tradition of the Bible in which Legge had been trained. It also raises the question of how this hermeneutic might have been applied by a Chinese— trained in this tradition—in their own interpretation of the Bible.7 I can’t help wondering if it offers any clues to how Hong Xiuquan, the Taiping leader (who had spent years studying the Chinese classics), interpreted the Bible.

The theme of an original Chinese monotheism, a prisca theologia (ancient theology), is a recurring element in missionary thinking. (I heard it stated with full conviction by my own grandfather, a second-generation missionary to China and Taiwan.) It takes a variety of forms. One of them is the claim that elements of the biblical story have, from antiquity, become embedded in various Chinese characters.

A few years ago I learned that the Scottish missionary Thomas Torrance, father of theologian Thomas F. Torrance, maintained that the Qiang people of western China, bordering Tibet, were descendants of a “lost tribe” of Israelites. Torrance tells of his experience with these people and spells out his theory in China’s First Missionaries: Ancient Israelites (1937), and his son commended the view in a 1988 reissue of the book.8

I find these theories highly speculative. But the deep history of China suggests all sorts of mysteries. And we can see the evangelistic appeal of these arguments in their providing an end run around the antiquity of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism by pointing to an ancient bedrock of Chinese monotheism.

Years after his association with Hong Rengan, Legge and some companions, on a trip to the Temple of Heaven in Peking, would ascend the Altar of Heaven, where the emperor yearly made a burnt bull offering to Shangdi. Standing barefoot, forming a circle, and holding hands, Legge and his companions sang the Doxology.

While this was controversial in missionary circles, the underlying rationale and sentiment would have resonated deeply with Taiping theology. The true and foundational religion of China was the worship of the Most High God.

Next, we return to the story of the Taiping!

For a recent and multi-faceted view of Legge, see the essays in Alexander Chow ed., Scottish Missions to China: Commemorating the Legacy of James Legge (1815-1897) (Brill, 2022).

Jonathan D. Spence, God’s Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan (New York: Norton, 1996), 270.

Lauren F. Pfister, “Some New Dimensions in the Study of the Works of James Legge (1815-1897),” Sino-Western Cultural Relations Journal 12 (1990):48-49; cited in Spence, God’s Chinese Son, 271.

Lauren F. Pfister, “The Legacy of James Legge,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 22.2 (1998), 77-82. See, e.g., James Legge, The Religions of China: Confucianism and Taoism Described and Compared with Christianity (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1880)

See Alexander Chow, “Finding God’s Chinese Name: A Comparison of the Approaches of Matteo Ricci and James Legge” in Scottish Missions to China: Commemorating the Legacy of James Legge (1815-1897), ed., Alexander Chow (Brill, 2022), 213-228, esp. 224-225.

James Legge, Sacred Books of the East, Part II: The Yi King, trans. James Legge, ed. F. Max Muller. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1899), xv. See also James Legge, The Religions of China: Confucianism and Taoism Described and Compared with Christianity (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1880), 7.

This has not gone unnoticed. See Chloe Starr, Chinese Theology: Text and Context (Yale University Press, 2016), 252-259.

(London: Thynne & Co, 1937). Republished and edited by Thomas F. Torrance, with new Introduction (Chicago: Daniel Shaw, 1988). https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.237017/page/n3/mode/1up?view=theater

This is another fascinating post, Dan. (I'm pretty sure that I first learned of Legge via reading Pound!)