My discovery that my great grandparents, Jimmy and Sophie Graham, spent their first month in China with Hampden and Pauline DuBose was a breakthrough in my understanding their introduction to missionary life in China. Dubose wrote and published a good deal (in English and Mandarin), and some of it offers concrete insights into what he would have imparted to these young missionaries.

The Grahams were fortunate to have Hampden and Pauline DuBose orienting them to Chinese culture and missionary work. Their month in Suzhou was to be a formative one. Some forty-five years later Jimmy would reflect on “dear old Dr. H. C. Dubose”: “He was street chapel preacher par excellence, itinerator, writer loyal to God and to friends to the last ditch.” Of his time spent with DuBose, Jimmy declared he “never got over the inspiration it was to me and the impetus to do wide preaching of the gospel.”[1]

While Jimmy was a student at Virginia’s Hampden Sydney College, he had heard DuBose speak about China and had met him. Pauline McAlpine DuBose and Hampden Coit DuBose had arrived in China in 1872, some eighteen years prior to the Grahams. They were among the early Southern Presbyterian missionaries in China, as the Southern Presbyterian church was getting back on its feet after the U.S. Civil War. Hampden would remain in Suzhou until his death in 1910, just before the fall of the Qing dynasty. Pauline continued the ministry in Suzhou until 1914. Three of their children returned to China as missionaries. Hampden would come to be regarded as one of the outstanding figures in the earlier generation of Southern Presbyterian missionaries in China.

Hampden DuBose was remarkably productive. His book Preaching in Sinim[2] (1893) was an invitation and guide for young missionaries in China. His tireless work in preaching the gospel is displayed as he gives advice and shares his experience in speaking in city chapels, marketplaces, and country settings. He seems to have been a constant student of Chinese language and culture.

In 1886 he published The Dragon, Image, and Demon, a treatise on the three religions of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Written from a traditional Protestant missionary’s perspective, it gives us a window into how many Southern Presbyterian missionaries would have viewed the religious world of their Chinese neighbors. But he also produced a number of publications in Chinese, including The Street-Chapel Pulpit, Illustrated Life of Christ, The Catechism of the Three Religions, as well as commentaries on select New Testament books.

DuBose would rise to some prominence when he co-founded, and became the first president of the Anti-Opium League in China. Beginning in 1896, the League marshaled likeminded missionaries and Christian medical workers in opposing the deadly opium trade in China. In 1899 the League published Opinions of Over 100 Physicians on the Use of Opium in China, which had a great impact. We shall return to this initiative later, but it is a measure of DuBose’s energy and the wide scope of his missionary vision that he vigorously took on the great social and systemic evil of the opium trade. It is one indicator of how these nineteenth-century missionaries combined evangelism with social work.

For one month the young missionaries were under the DuBose mentorship. Some of what Hampden imparted, to Jimmy in particular, would later be found in Preaching in Sinim. Published three years later in 1893, DuBose was undoubtedly writing the book in 1889-90.[3] DuBose, as were many other missionaries of that era, was a great believer in the establishment of city chapels. DuBose’s chapel (which seems to have been attached to his home) was situated on a prominent flag-stone-paved street,[4] the Yang Ho Yang. Such chapels were standard venues for Christian evangelistic preaching, and we have already encountered these in our tour of the old walled city of Shanghai. Like a Chinese storefront, they were open to the narrow street, and easily entered and exited by curious passersby.

A chapel service would begin with gospel songs and prayer, and a few people would be assembled. And DuBose knew his audience:

The speaker commences, and all eyes are fixed upon him. He warms up in his subject, and soon the vacant sittings are filled, and fifty or a hundred are giving ear to the word. The attention is unwearied. Here sits the countryman, resting on his journey; the artisan, who wishes to know something of this strange cult; the clerk, who likes to hear the foreigner speak his own language; the merchant from a distant province; the passing traveler, with only five minutes to sit, and the mandarin’s assistant, wishing to while away an hour; the coolie in his sandals, and gentlemen in robed satin; the old woman who goes to the temple to worship, and the scholar, full of pride and prejudice, armed against the teachers and teachings of Christianity…. Some listen as to a lecture on a literary theme, others seek for something better than the religions they possess.[5]

The audience’s attention might be broken by a passing mandarin’s retinue, or a wedding or funeral procession. But the chapel preacher flexes with these circumstances. The chapel preacher could not count on a continuous hearing. Sometimes the group is restless, other times they give their rapt attention. And an ebb and flow of listeners was expected. So DuBose offered a clever way of approaching the task: “The mode of address is not so much one long sermon as a series of short ones, resembling on a narrow-gauge railway a train of little coaches coupled together.”[6]

The chapel should include a room for prayer and for private conversations with inquirers. Here is where meaningful conversations and conversions were likely to occur, and for DuBose the heart of his mission was securing men and women for God’s kingdom. He also recommends “a reading-room and book-stall well supplied with Christian and scientific literature,” which should be made as comfortable as possible.[7]

This companionship of Christian truth with Western science might surprise twenty-first-century observers, but it was a common theme of the missionary mind in China of that era. For the gospel was joined with the benefits of Christian culture, which had bloomed in the progress of Western science and technology.[8] All this made good sense in a city such as Suzhou, which was a center of intellectual activity.

Obviously, DuBose was eager to convert. But he was no one’s fool. While back in his gospel-saturated homeland a few weeks of revival services might bear fruit, “here these great cities need a protracted meeting of three or four centuries.”[9] His Calvinistic trust in the patient providence of God, tempered by a post-millennial cast of mind, was seasoned too by the layered antiquity of Chinese society lying all around him. Practically speaking, he advocated the long view. “For we do not labor by the day, or the month, or the year.”[10] “During the course of twenty years, one million men may come into a chapel daily opened, and hear something of the plan of salvation. It is the Master’s scheme for leavening a great lump.”[11] While back in America A. T. Pierson was enlisting college students with the urgency of the evangelizing the world “in this generation,” out in Suzhou, China, DuBose was steadily committed to the long game.

DuBose went so far as to claim the chapel as an “enlightening” and “civilizing agency,” ever so gradually eroding prejudices against Western institutions and breaching the wall of “Chinese obstructiveness.”[12] He recognized that a seed planted in a traveler stopping into his Suzhou chapel might take time to bear fruit, perhaps years later in far-away Peking.

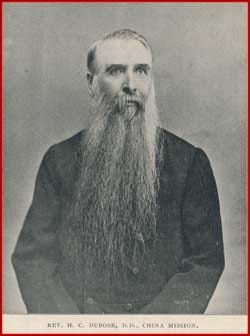

Forty-five years later, Jimmy Graham attested to the wide-ranging effectiveness of DuBose’s Yang Yo Hang chapel in Suzhou: “I have met people over the far northern stretches of the province who had heard the Gospel there from ‘an old man with a long beard.’”[13]

In our next episode we learn more about this “old man with a long beard.”

[1] James R. Graham, “These Seventy Years,” 2-3.

[2] “Sinim” is found in the Bible at Isaiah 49:12, and was then thought to refer to China: “Behold, these shall come from far: and, lo, these from the north and from the west; and these from the land of Sinim” (King James Version).

[3] Hampden C. DuBose, Preaching in Sinim: or, The Gospel to the Gentiles, with Hints and Helps for Addressing a Heathen Audience (Richmond: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1893). The publisher acknowledges that the manuscript was in hand “some two years since” but “has, for sufficient cause, been delayed.”

[4] DuBose, Beautiful Soo, 17.

[5] DuBose, Preaching in Sinim, 52-53.

[6] DuBose, Preaching in Sinim, 54.

[7] DuBose, Preaching in Sinim, 57-58.

[8] We shall return to this later. It has been striking to me how often this theme shows up, often in unspoken and implicit ways.

[9] DuBose, Preaching in Sinim, 56.

[10] DuBose, Preaching in Sinim, 61.

[11] DuBose, Preaching in Sinim, 58.

[12] DuBose, Preaching in Sinim, 59.

[13] James R. Graham, “These Seventy Years in China” (unpublished paper, 1936), 2-3.