"William McKinley Is Having a Moment"

Missions, American Empire, and the Gilded Hand of Providence

If you have been following me, you will recall the title of my post of a couple weeks ago: “I Would Not Exchange It … for a Seat in the President’s Cabinet.” That was a quote from my great grandfather Jimmy Graham, written from his seat on a wind-tossed boat over one hundred years ago. He was commenting on his satisfaction with his life as an itinerant evangelist in China. That bit about “the President’s Cabinet”—written to supporting Presbyterian churches back home—is something you’d never hear from a Protestant missionary in 2024, but it was full of resonance in 1921. In that era, American Protestant missionaries had exceptional access to the seats of political power.

I’ve been wanting to say something about this. And then I read the opening line of Heather Cox Richardson’s Substack (“Letters from an American,” October 5, 2024): “William McKinley is having a moment (which I confess is a sentence I never expected to write).”

Yes, thanks to He Who Shall Not Be Named, and the question of tariffs, President McKinley is popping up in the news. And McKinley had been on my mind as well. It had something to do with my reading of Emily Conroy-Krutz’s Missionary Diplomacy: Religion and Nineteenth-Century American Foreign Relations (Cornell University Press, 2024). But it goes back further than that.

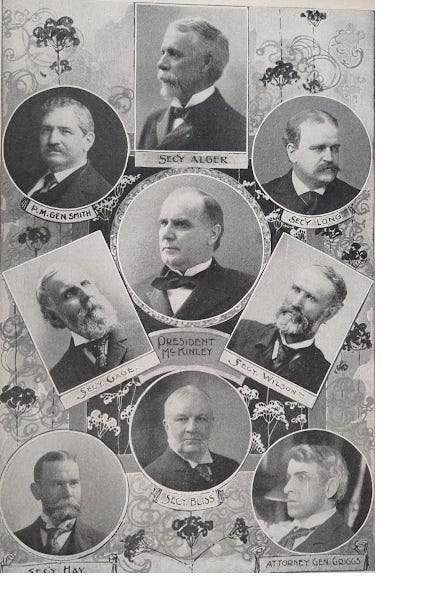

My first encounter with President McKinley’s intersection with Protestant missions was in the mid-1980s, when I was teaching in a seminary in the Philippines. I had come across Gerald H. Anderson’s essay in Studies in Philippine Church History,1 in which he quotes the memorable piece from William McKinley in 1898. McKinley was telling a delegation from the missionary committee of the Methodist Church how he settled on taking the Philippines in the Spanish-American War. McKinley was himself a Methodist.

Here is what McKinley said:

The truth is I didn’t want the Philippines, and when they came to us as a gift from the gods, I did not know what to do with them. … I sought counsel from all sides—Democrats as well as Republicans—but got little help…. I walked the floor of the White House night after night until midnight; and I am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen, that I went down on my knees and prayed Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night.

The answer arrived (likely swift on the heels of suggestion from the religious press):

And one night late it came to me this way—I don’t know how it was, but it came: (1) that we could not give them back to Spain—that would be cowardly and dishonorable; (2) that we could not turn them over to France or Germany—our commercial rivals in the Orient—that would be bad business and discreditable; (3) that we could not leave them to themselves—they were unfit for self-government—and they would soon have anarchy and misrule over there worse than Spain’s was; and (4) that there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow-men for whom Christ died. And then I went to bed, and went to sleep, and slept soundly, and the next morning I sent for the chief engineer of the War Department (our map-maker), and I told him to put the Philippines on the map of the United States, and there they are, and there they will stay while I am President.2

Of this Reinhold Niebuhr would later write, “The fiction that the fortunes of war had made us the unwilling recipients and custodians of the Philippine Islands was quickly fabricated and exists to this day.” And he refers to “Mr. McKinley’s hypocrises” being “a little more than usually naive.” Writing in 1932, Niebuhr saw the mask slipping from the noble intention of the USA preparing the Filipinos for democracy and independence. Since the status of the Philippines as an independent nation would put the considerable American business interests in Philippine sugar on the “outside of the American tariff wall.”3 In other words, Philippine sugar would be priced out of competition in the USA. (I see historical justice in Alaska’s Mt. McKinley now being called Denali.)

Tariffs and sugar aside, McKinley’s rationale, expressed to the Methodist mission leadership, was my own memorable encounter with the intersection of Protestant missions and American empire. And if my heart was briefly warmed by McKinley’s Christian piety, the entanglement of Christian missions with American political interests was unsettling.

Putting down Anderson’s book, I had only to reach for Renato Constantino’s The Philippines: A Past Revisited to get a Philippine patriot’s view of the matter. And for Constantino, it runs like this: While Western powers were carving up the “melon” of China, the United States, late to the game, wanted her piece. And the Philippines was a very attractive base and springboard from which “to penetrate China economically and evangelistically.” (Constantino, 289) So, through the Spanish-American War, the Philippines was transferred from Spanish rule to American rule. And Constantino knows that tariff-free sugar was also a big motivation.4

Anderson also tells us that in 1898 Rev. John Henry Barrows (D.D.), president of Oberlin College, spoke of the “divine mission” of America. The outcome of the Spanish-American War, with Spain’s ceding Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the U.S. was clearly providential. “God has been speaking of late with a voice which nothing can drown. The unexpected has happened. This means that God has intervened.” During the winter of 1898, Barrows delivered a series of lectures at Union Theological Seminary in New York City entitled “The Christian Conquest of Asia.” There he maintained that “The United States possesses at the present hour stepping stones for its commercial and moral pathway across the Pacific.” Furthermore, “God has placed us, like Israel of old, in the centre of the nations.… And wherever on pagan shores the voice of the American missionary and teacher is heard, there is fulfilled the manifest destiny of the Christian Republic.”5

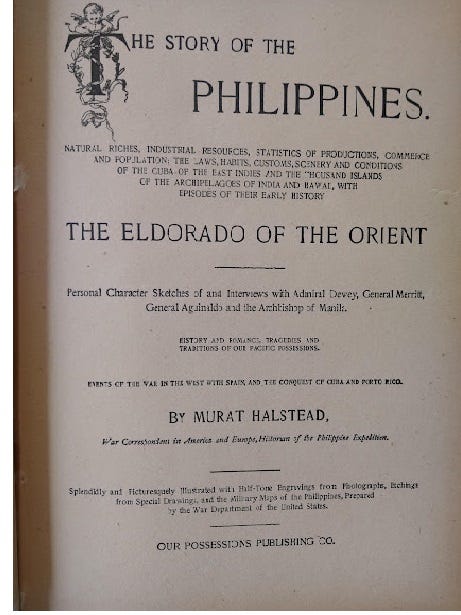

Within a year or so of reading Anderson on McKinley, I was in a used bookstore in downtown Seattle and happened on a The Story of the Philippines.6 And for $3.50 I was given a 512-page, illustrated entrance into a national celebration of the U.S. receiving the gift of the Philippines, “The Eldorado of the Orient.” I still have the book. Here are just a few of its rhetorical flourishes, from a victory celebration at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall:

Archbishop John Ireland carries on like a Protestant celebrating this victory over Catholic Spain:

The world to-day admires and respects America. The young giant of the West, heretofore neglected and almost despised in his remoteness and isolation, has begun to move as becomes his stature; the world sees what he is and pictures what he may be…. All this does not happen by chance or accident. An all-ruling Providence directs the movements of humanity. What we witness is a momentous dispensation from the master of men…. So today we proclaim a new order of things has appeared.7

Judge Emory Speer of Georgia uncorks his Southern rhetorical powers:

But two months ago the flagship of Admiral Dewey steamed slowly into the battle line at Manila. As she passed the British flagship Immortalite its band rang out the inspiring air “See the Conquering Hero Comes,” and as the gorgeous ensign of the republic was flung to the breeze at the peak of the Olympia there now came thrilling o’er the waters from our kinsmen’s ship the martial strains of the “Star Spangled Banner…. Well may we exclaim with the royal poet of Israel: “Oh, sing unto the Lord a new song, for he hath done marvelous things; his right hand and his his holy arm hath gotten him the victory.”

America! Humane in the hour of triumph, gentle to the vanquished, grateful to the Lord of Hosts, a reunited people forever.8

Then “the band burst into strains of ‘Dixie’ in honor of the Southern birth of Judge Speer.”

President McKinley was present and concluded with a few words “of simple thanks and significant augury,” including this:

My countrymen, the currents of destiny flow through the hearts of the people. Who will check them? Who will divert them? Who will stop them? And the movements of men, planned by the master of men, will never be interrupted by the American people.9

Well, this particular chapter of imperial destiny was sharply arrested, not by the American people, but by the Empire of Japan in December 1941.

History is endlessly complicated. And human motives and actions, and the contexts in which they are formed, are equally as complicated. And as I have delved into the early history of Protestant missions and U.S. interests in China, I am repeatedly struck by the intertwining of gospel and nation. And as the McKinley anecdote displays, it was not just at the front lines of missionary work, but it reached into the White House as well.

One instance of this came in 1913, when President Woodrow Wilson offered the ambassadorship to China to the international missions leader John R. Mott. (Mott declined.) As another example, the Southern Presbyterian missionary Samuel I. Woodbridge (we met him when the Grahams were beginning language study), was married to Woodrow Wilson’s niece. And he felt free to advise the President on matters related to China. Wilson, himself a Southern Presbyterian and a son of the manse, was sympathetic to the missionary effort in China, and listened. Another Southern Presbyterian missionary (and “missionary kid”), the educator and New Testament scholar John Leighton Stuart, was also associated with Woodrow Wilson, and later served as U.S. Ambassador to China from 1946 to 1949. And there are many other instances of American missionaries playing the role of statesmen, with diplomatic and political involvements, including the “China Lobby” of the 1940s and 1950s.

Reading this in 2024, I imagine someone drawing a connection with the variety of contemporary movements called “Christian nationalism,” and current talk of an incipient American “theocracy.” To be sure, I’m not a fan of any of that. And I find it deeply corrosive of the Christian gospel. But the terrain is vastly different today.

It is difficult for us to get our heads around that world of over a century ago. For the understanding of America’s providential mission across the Pacific was a mainstream idea, advocated in what came to be known as Mainline Protestantism. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the enthusiasm for Protestant missions was strong, recruiting students from some of America’s best universities.

And I should clarify that I too believe in divine providence. But I’m deeply skeptical of those who confidently claim to discern its pattern in contemporary events. And all the more when this providence just happens to align with self-serving, nation-serving, or empire-serving ends.

I want to return to this topic missionary diplomacy, with a look at Emily Conroy-Krutz’s book. But let me leave you with one final nugget. Somewhere in my disorganized archive of newspaper clippings I have a report of a Southern Presbyterian missionary to China (a woman, and a shirttail relative of mine), probably in the 1920s, addressing a missions group back in the States. She tells of a Chinese woman who said:

“When I get to heaven, I am going to tell Jesus that I am an American.”

Ouch!

Gerald H. Anderson "Providence and Politics behind Protestant Missionary Beginnings in the Philippines” in Studies in Philippine Church History (Cornell University Press, 1969), 279-300. Anderson had taught at Union Theological Seminary, Manila, in the 1960s. This brings back a happy memory from the fall of 1990, when I visited him at the Overseas Ministries Studies Center, then in New Haven, Connecticut.

Anderson, “Providence and Politics,” 292-293. The interview was actually published three years after the fact, in The Christian Advocate (January 22, 1903): 137-138.

Reinhold Niebuhr, Moral Man and Immoral Society (Charles Scribner’s, 1932), 102-103.

Renato Constantino, The Philippines: A Past Revisited (Manila: Renato Constantino, 1975), 289-291. Constantino also comments on McKinley’s tariff enthusiasm: “If the United States were to come into possession of sugar-producing territories, their produce would not be subject to the new tariff provisions and could enter the U.S. duty-free.”

Quoted in Anderson, “Providence and Politics,” 294. The lectures were published as The Christian Conquest of Asia (New York, 1899).

Murat Halstead, The Story of the Philippines (Our Possessions Publishing Co, 1898).

Halstead, The Story, 286.

Halstead, The Story, 295.

Halstead, The Story, 296-297.